Cayley–Purser algorithm

The Cayley–Purser algorithm was a public-key cryptography algorithm published in early 1999 by 16-year-old Irishwoman Sarah Flannery, based on an unpublished work by Michael Purser, founder of Baltimore Technologies, a Dublin data security company. Flannery named it for mathematician Arthur Cayley. It has since been found to be flawed as a public-key algorithm, but was the subject of considerable media attention.

Contents |

History

During a work-experience placement with Baltimore Technologies, Flannery was shown an unpublished paper by Michael Purser which outlined a new public-key cryptographic scheme using non-commutative multiplication. She was asked to write an implementation of this scheme in Mathematica.

Before this placement, Flannery had attended the 1998 ESAT Young Scientist and Technology Exhibition with a project describing already existing crytographic techniques from Caesar cipher to RSA. This had won her the Intel Student Award which included the opportunity to compete in the 1998 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in the United States. Feeling that she needed some original work to add to her exhibition project, Flannery asked Michael Purser for permission to include work based on his cryptographic scheme.

On advice from her mathematician father, Flannery decided to use matrices to implement Purser's scheme as matrix multiplication has the necessary property of being non-commutative. As the resulting algorithm would depend on multiplication it would be a great deal faster than the RSA algorithm which uses an exponential step. For her Intel Science Fair project Flannery prepared a demonstration where the same plaintext was enciphered using both RSA and her new Cayley-Purser algorithm and it did indeed show a significant time improvement.

Returning to the ESAT Young Scientist and Technology Exhibition in 1999, Flannery formalised Cayley-Purser's runtime and analyzed a variety of known attacks, none of which were determined to be effective.

Flannery did not make any claims that the Cayley-Purser algorithm would replace RSA, knowing that any new cryptographic system would need to stand the test of time before it could be acknowledged as a secure system. The media were not so circumspect however and when she received first prize at the ESAT exhibition, newspapers around the world reported the story that a young girl genius had revolutionised cryptography.

In fact an attack on the algorithm was discovered shortly afterwards but she analyzed it and included it as an appendix in later competitions, including a Europe-wide competition in which she won a major award.

Overview

Notation used in this discussion is as in Flannery's original paper.

Key generation

Like RSA, Cayley-Purser begins by generating two large primes p and q and their product n, a semiprime. Next, consider GL(2,n), the general linear group of 2×2 matrices with integer elements and modular arithmetic mod n. For example, if n=5, we could write:

This group is chosen because it has large order (for large semiprime n), equal to (p2-1)(p2-p)(q2-1)(q2-q).

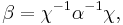

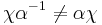

Let  and

and  be two such matrices from GL(2,n) chosen such that

be two such matrices from GL(2,n) chosen such that  . Choose some natural number r and compute:

. Choose some natural number r and compute:

The public key is  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . The private key is

. The private key is  .

.

Encryption

The sender begins by generating a random natural number s and computing:

Then, to encrypt a message, each message block is encoded as a number (as in RSA) and they are placed four at a time as elements of a plaintext matrix  . Each

. Each  is encrypted using:

is encrypted using:

Then  and

and  are sent to the receiver.

are sent to the receiver.

Decryption

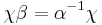

The receiver recovers the original plaintext matrix  via:

via:

Security

Recovering the private key  from

from  is computationally infeasible, at least as hard as finding square roots mod n (see quadratic residue). It could be recovered from

is computationally infeasible, at least as hard as finding square roots mod n (see quadratic residue). It could be recovered from  and

and  if the system

if the system  could be solved, but the number of solutions to this system is large as long as elements in the group have a large order, which can be guaranteed for almost every element.

could be solved, but the number of solutions to this system is large as long as elements in the group have a large order, which can be guaranteed for almost every element.

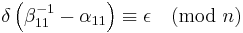

However, the system can be broken by finding a multiple  of

of  by solving the congruence:

by solving the congruence:

for  , where

, where  are the top-left elements of

are the top-left elements of  . Since any multiple of

. Since any multiple of  can be used to decipher, this presents a fatal weakness for the system that has not yet been reconciled.

can be used to decipher, this presents a fatal weakness for the system that has not yet been reconciled.

This flaw does not preclude the algorithm's use as a mixed private-key/public-key algorithm, if the sender transmits  secretly, but this approach presents no advantage over the common approach of transmitting a symmetric encryption key using a public-key encryption scheme and then switching to symmetric encryption, which is faster than Cayley-Purser.

secretly, but this approach presents no advantage over the common approach of transmitting a symmetric encryption key using a public-key encryption scheme and then switching to symmetric encryption, which is faster than Cayley-Purser.

References

- Sarah Flannery. Cryptography: An Investigation of a New Algorithm vs. the RSA. (original pdf)

- Sarah Flannery and David Flannery. In Code: A Mathematical Journey. ISBN 0-7611-2384-9

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\left[\begin{matrix}0 & 1 \\ 2 & 3\end{matrix}\right] %2B

\left[\begin{matrix}1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4\end{matrix}\right] =

\left[\begin{matrix}1 & 3 \\ 5 & 7\end{matrix}\right] =

\left[\begin{matrix}1 & 3 \\ 0 & 2\end{matrix}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7bca5394f35462106e9c995c206348fa.png)

![\left[\begin{matrix}0 & 1 \\ 2 & 3\end{matrix}\right]\left[\begin{matrix}1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4\end{matrix}\right] =

\left[\begin{matrix}3 & 4 \\ 11 & 16\end{matrix}\right] =

\left[\begin{matrix}3 & 4 \\ 1 & 1\end{matrix}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/da408df349c13c6af78e99b16bd42bc6.png)